Charitable Giving

Charitable giving can play an important role in many estate plans. Philanthropy cannot only give you great personal satisfaction, it can also give you a current income tax deduction, let you avoid capital gains tax, and reduce the amount of taxes your estate may owe when you die.

There are many ways to give to charity. You can make gifts during your lifetime or at your death. You can make gifts outright or use a trust. You can name a charity as a beneficiary in your will, or designate a charity as a beneficiary of your retirement plan or life insurance policy. Or, if your gift is substantial, you can establish a private foundation, community foundation, or donor-advised fund.

Making outright gifts

An outright gift is one that benefits the charity immediately and exclusively. With an outright gift you get an immediate income and gift tax deduction.

Tip: Make sure the charity is a qualified charity according to the IRS. Get a written receipt or keep a bank record for any cash donations, and get a written receipt for any property other than money.

Will or trust bequests and beneficiary designations

These gifts are made by including a provision in your will or trust document, or by using a beneficiary designation form. The charity receives the gift at your death, at which time your estate can take the income and estate tax deductions.

Charitable trusts

Another way for you to make charitable gifts is to create a charitable trust. You can name the charity as the sole beneficiary, or you can name a non-charitable beneficiary as well, splitting the beneficial interest (this is referred to as making a partial charitable gift). The most common types of trusts used to make partial gifts to charity are the charitable lead trust and the charitable remainder trust.

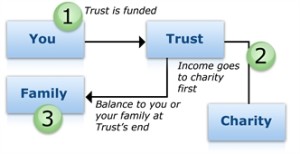

Charitable lead trust

A charitable lead trust pays income to a charity for a certain period of years, and then the trust principal passes back to you, your family members, or other heirs. The trust is known as a charitable lead trust because the charity gets the first, or lead, interest.

A charitable lead trust can be an excellent estate planning vehicle if you own assets that you expect will substantially appreciate in value. If created properly, a charitable lead trust allows you to keep an asset in the family and still enjoy some tax benefits.

How a Charitable Lead Trust Works

Example: John, who often donates to charity, creates and funds a $2 million charitable lead trust. The trust provides for fixed annual payments of $100,000 (or 5% of the initial $2 million value) to ABC Charity for 20 years. At the end of the 20-year period, the entire trust principal will go outright to John’s children. Using IRS tables and assuming a 2.0% Section 7520 rate, the charity’s lead interest is valued at $1,635,140, and the remainder interest is valued at $364,860. Assuming the trust assets appreciate in value, John’s children will receive any amount in excess of the remainder interest ($364,860) unreduced by estate taxes.

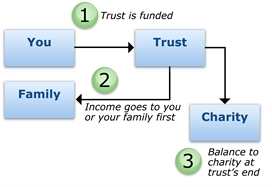

Charitable remainder trust

A charitable remainder trust is the mirror image of the charitable lead trust. Trust income is payable to you, your family members, or other heirs for a period of years, then the principal goes to your favorite charity.

A charitable remainder trust can be beneficial because it provides you with a stream of current income–a desirable feature if there won’t be enough income from other sources.

How a Charitable Remainder Trust Works

Example: Jane, an 80-year-old widow, creates and funds a charitable remainder trust with real estate currently valued at $1 million, and with a cost basis of $250,000. The trust provides that fixed quarterly payments be paid to her for 20 years. At the end of that period, the entire trust principal will go outright to her husband’s alma mater. Using IRS tables and assuming a 2.0% Section 7520 rate, Jane receives $50,000 each year, avoids capital gains tax on $750,000, and receives an immediate income tax charitable deduction of $176,298, which can be carried forward for five years. Further, Jane has removed $1 million, plus any future appreciation, from her gross estate.

Private family foundation

A private family foundation is a separate legal entity that can endure for many generations after your death. You create the foundation, then transfer assets to the foundation, which in turn makes grants to public charities. You and your descendants have complete control over which charities receive grants. But, unless you can contribute enough capital to generate funds for grants, the costs and complexities of a private foundation may not be worth it.

Tip: One rule of thumb is that you should be able to donate enough assets to generate at least $25,000 a year for grants.

Community foundation

If you want your dollars to be spent on improving the quality of life in a particular community, consider giving to a community foundation. Similar to a private foundation, a community foundation accepts donations from many sources, and is overseen by individuals familiar with the community’s particular needs, and professionals skilled at running a charitable organization.

Donor-advised fund

Similar in some respects to a private foundation, a donor-advised fund offers an easier way for you to make a significant gift to charity over a long period of time. A donor-advised fund actually refers to an account that is held within a charitable organization. The charitable organization is a separate legal entity, but your account is not–it is merely a component of the charitable organization that holds the account. Once you transfer assets to the account, the charitable organization becomes the legal owner of the assets and has ultimate control over them. You can only advise–not direct–the charitable organization on how your contributions will be distributed to other charities.